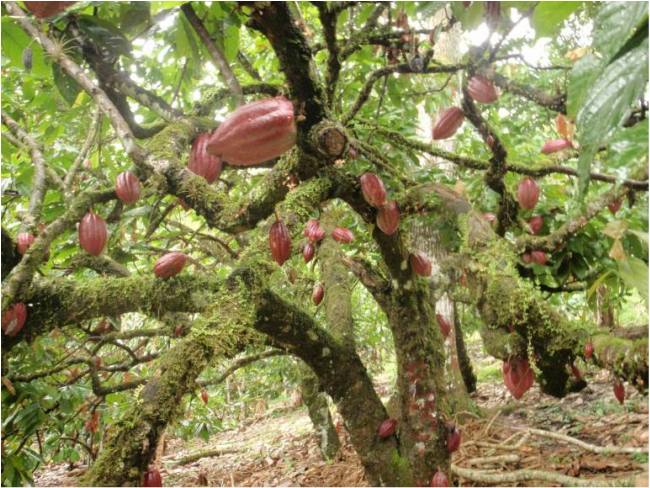

Quilile mother trees (used for grafting branches of fine cacao varieties to faster-growing cacao starter plants)—Quilile, Matagalpa, Nicaragua

Historically, very few Nicaraguans have called themselves cacao farmers. For most producers, cacao is the third or fourth crop produced on their farms (coffee, cattle ranching, and sugar cane are typical primary crops). The vast majority of cacao in Nicaragua can be called a “patio crop,” meaning that farmers tend to have a few cacao trees in their yard and harvest the cacao that comes from these few trees, dry their production with little or no fermentation, and sell informally in local markets at low prices. This “red cacao” is then shipped (usually informally) to larger regional markets in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico and is eventually used in a variety of local Mesoamerican products such as tejate, mole, and artisan chocolate.

With the governmental change in 1990, numerous Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) appeared in Nicaragua with humanitarian aid and development projects. Cacao-promotional projects were typical, as the crop was mentioned as an alternative product for small-holder rural farms. The myth that the cacao tree basically needs no maintenance persisted, and several thousand additional hectares of cacao were planted. While there was a notable increase in the overall volume of cacao produced, these programs failed to address two key problems with cacao production in Nicaragua: First, the attitudes of local farmers towards the crop remained the same (cacao as third or fourth priority, therefore harvest whatever the plant gives with little or no maintenance). And second, little was done to develop the entire commodity chain. Little emphasis was placed on quality post-harvest processing, viable commercialization options for producers, or on established companies focused on exporting cacao outside of the Mesoamerican region.

During the 2000’s the cacao sector developed further: cooperatives were formed, NGOs supported training sessions for farmers, a few cacao growers became organic/fair trade certified, and some larger companies began to export fermented Nicaraguan cacao. Other investors came to Central America to start genetically-specific cocoa initiatives. The Proyecto Centroamericano de Cacao (PCC), a CATIE-led initiative across Central America promoted hybrid, disease-resistant clones (R-1, R-4, R-6, and PMCT-58) without much consideration for unique and native flavors. While many of these initiatives helped further the cause for Nicaraguan cacao, they increased the potential for the few remaining heirloom cacao groves to disappear as hybrids are promoted.

While the sector did grow during the first decade of the 21st Century, a few crucial elements tended to lag behind. Specifically, post-harvest processing was never a high priority, and Nicaraguan cacao thus tended to be poorly regarded internationally. In fact, not until 2011 did the major cooperatives begin to collect fresh cacao and ferment in controlled, centralized facilities.

Even with this new emphasis on post-harvest processing, there is much to be learned by both growers and processors as the Nicaraguan cacao sector develops. Cacao Bisiesto prides itself on high-quality fermenting and drying practices that remove bitterness and acidity from cacao beans, as well as on building productive relationships with farmers that increase their crop management knowledge and give them fair prices for their product.

Cacao Bisiesto is committed to raising awareness of the significance of Nicaragua's cacao to its land owners and to the world chocolate market.

With the governmental change in 1990, numerous Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) appeared in Nicaragua with humanitarian aid and development projects. Cacao-promotional projects were typical, as the crop was mentioned as an alternative product for small-holder rural farms. The myth that the cacao tree basically needs no maintenance persisted, and several thousand additional hectares of cacao were planted. While there was a notable increase in the overall volume of cacao produced, these programs failed to address two key problems with cacao production in Nicaragua: First, the attitudes of local farmers towards the crop remained the same (cacao as third or fourth priority, therefore harvest whatever the plant gives with little or no maintenance). And second, little was done to develop the entire commodity chain. Little emphasis was placed on quality post-harvest processing, viable commercialization options for producers, or on established companies focused on exporting cacao outside of the Mesoamerican region.

During the 2000’s the cacao sector developed further: cooperatives were formed, NGOs supported training sessions for farmers, a few cacao growers became organic/fair trade certified, and some larger companies began to export fermented Nicaraguan cacao. Other investors came to Central America to start genetically-specific cocoa initiatives. The Proyecto Centroamericano de Cacao (PCC), a CATIE-led initiative across Central America promoted hybrid, disease-resistant clones (R-1, R-4, R-6, and PMCT-58) without much consideration for unique and native flavors. While many of these initiatives helped further the cause for Nicaraguan cacao, they increased the potential for the few remaining heirloom cacao groves to disappear as hybrids are promoted.

While the sector did grow during the first decade of the 21st Century, a few crucial elements tended to lag behind. Specifically, post-harvest processing was never a high priority, and Nicaraguan cacao thus tended to be poorly regarded internationally. In fact, not until 2011 did the major cooperatives begin to collect fresh cacao and ferment in controlled, centralized facilities.

Even with this new emphasis on post-harvest processing, there is much to be learned by both growers and processors as the Nicaraguan cacao sector develops. Cacao Bisiesto prides itself on high-quality fermenting and drying practices that remove bitterness and acidity from cacao beans, as well as on building productive relationships with farmers that increase their crop management knowledge and give them fair prices for their product.

Cacao Bisiesto is committed to raising awareness of the significance of Nicaragua's cacao to its land owners and to the world chocolate market.